For Richer Or For Poorer

man could do was pick dead fish

off the beach before the races.

Vanderbilt brought a beast

of a Mercedes that could do 92.

Later, he’d put $6 million into

paving the Vanderbilt Motor Parkway

to speed him from NYC, 45 miles

out on Long Island. In 1910,

Rockefeller, for all his Standard

Oil, loved watching Barney

Oldfield gassing up his Benz

to hit a record 131. Handsome

young men of daring could

do little without the money

to buy $6,000 worth of tires —

the price of 4 race treads,

even in the Depression. When

he came to town in the ’30s,

a guy like Bill France was

the opposite of a fat cat. He didn’t

have a dime enough to call

a sponsor and ask for money —

just fiddled with cars, opened

the throttle and let loose,

paving the way for generations

of working stiffs to not just watch

but enter their cars. Take Russ

Truelove, a heartthrob on

the track in the mid ’50s, out

there in his souped-up Mercury.

He could run flat out for a $5,000

purse, tearing up the beach, racing

north toward Junkyard Turn,

then south on A1A toward fame

and that small fortune. Fast cars,

at last, were for any good man’s

pleasure. “If we were lucky,”

Truelove waxed poetic, “we’d

hear the faint whisper of the surf,”

a siren’s call to speed as we

risked it all racing along

the beach. Later, he admitted

a driver couldn’t hear a thing

over the roar of the engine.

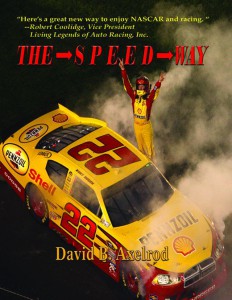

(For more by David Axelrod go to www.totalrecallpress.com or www.amazon.com.)