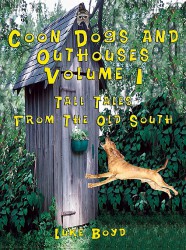

Promoting, Marketing and Advertising your title

Ol’ Raymond

By Luke Boyd

I never knew why we tacked the first part on. He surely was not old. I suppose it was a title of affection or endearment.

Ol’ Raymond was a red-bone coon hound and a credit to his breed. He was a big dog. I’m sure he seemed big to me because I was so small. But the pictures verify his size. Judging from the size of Gene, my brother, I was somewhere between three and four years old. In one, I am standing at his shoulder and Gene sits astride him like he’s riding a horse. The dog and I are about the same height. In another, he carries both of us on his back with ease. As I said, he was a big dog.

He was an outside dog. In that time and place, no one kept a dog in the house. He generally slept on one of the porches in warm weather. In the winter, he would scratch himself out a depression under the house on the south side of the chimney base and use the warm bricks for heat.

Ol’ Raymond was a very protective dog. As I roamed about the farm, I knew that I had nothing to fear from anything or anybody as long as he was with me. In fact, he was the protector of the whole family. My daddy was sharecropping a new-ground farm in the western part of the Delta toward the River. After crops were laid by and during the winter, he was away from home a lot doing carpentry work. We had an unpainted picket fence around the yard and I heard my mama say on more than one occasion, “No, we’re not afraid to be here by ourselves. Ol’ Raymond won’t let anyone inside that fence when Luke’s gone.” Ironically it was this protectiveness that would prove to be his undoing.

My daddy hunted a lot to put meat on the table. He also ran a trap line trapping mostly mink and raccoon for their pelts. I’m sure the skins didn’t bring much by today’s standards, but in the mid ’30s, any extra income was a bonus. There were usually several skins drying on stretcher boards out by the smokehouse.

He also went coon hunting at night with other men who had coon dogs. They would always come back with coons, but this type hunting was mostly for sport. This was where Ol’ Raymond really proved his mettle. Men would come from miles around to run their dogs with him, and I never tired of hearing the stories my daddy told about his prowess in the hunt. My favorite was his confrontation with Pegleg.

Pegleg was a big boar coon who ranged around the nearby bayous. He’d been trailed but never treed, seen but never caught. He got his name because of a missing paw. That leg ended in a stump which left a very distinctive track in the soft, swampy ground. My daddy theorized that the missing paw was chewed off by the coon himself when he got caught in a trap and could free himself no other way. Coons were known to do that.

Anyway, by this time Pegleg was old and grizzled and smart. He knew how to avoid traps and he also knew any number of ways to throw off a pack of dogs who were hot on his trail. Sometimes he would backtrack on his trail and go off in another direction through the trees leaving no scent on the ground. Or he would swim down a creek or crisscross a creek several times to cause the dogs to lose his trail in the water. As a result, Pegleg had never been treed.

One night the men turned the dogs loose and they struck a hot trail immediately. They ran almost in a circle and soon their trailing bark changed to one that told the men that they had their quarry at bay very close by. The hunters hurried toward the sound and came to the bank of a large bayou. The coon’s tracks showed the missing paw. It was Pegleg. Only he wasn’t up a tree. He was too smart for that. The dogs had apparently picked up his trail very close to him and pushed him so hard that he had no opportunity to use any of his tricks. But the old coon wasn’t giving up by any means. The light from the carbide headlamps reflected off his eyes as he sat on a log out in deep water waiting. The other dogs stood on the bank barking. Ol’ Raymond was swimming out to get the coon.

Now, the last place a dog wants to confront a coon is in water. A coon will usually wrap himself around the dog’s head, forcing it under the water while keeping his own above the surface. In a very few minutes a big coon could drown a dog or whip him so badly that he would leave the fray.

Of course, my daddy had a gun and could have shot the coon, but the dog had brought him to bay and the sporting thing was to allow the dog to try to finish the job even if he got killed in the process.

But Ol’ Raymond had fought coons in water before and come out the winner. Instead of trying to hold his head up when the coon climbed aboard, he would do the opposite and push the coon under water, causing him to release his hold to get to the surface. After two or three repetitions of this, Ol’ Raymond would get the coon worn down and get his jaws on the coon’s neck, ending the fight. But this was not just any coon.

Sure enough, when Ol’ Raymond got to the log, Pegleg attacked. He jumped on the dog’s head and began biting him about the ears and neck. Ol’ Raymond rolled him under and broke the hold. They surfaced and the process was repeated and then repeated again, and again, and again, until my daddy lost count. He confessed that at that point he was wishing he’d shot the coon, but it was too late for that. The two combatants were throwing up so much spray and foam from the murky water and were so closely intertwined that a shot would just as likely hit the dog as the coon. The fight was both furious and long–longer than any fight like this these men had ever seen. Suddenly, the coon let out a squeal that told them that Ol’ Raymond had the coon in his jaws and the fight was over. He tried to drag Pegleg to the bank but was so exhausted that the men had to wade out and help him. The men vowed that they had never seen such a fight in all their years of coon hunting and Ol’ Raymond’s fame spread even farther. The tear in his ear and the cuts on his face and head would heal and be worn as proudly as a dueling scar–the marks of a coon dog who had fought and won.