The Watcher

By by Kathleen A. Ryan/compiled by John Wills

the one concerning an elderly resident who hasn’t been seen in a while. I met with the caller in front of the cottage of Emma Brown (all names have been changed to protect confidentiality), a 75-year-old divorcee who lived alone in a residential neighborhood of East Northport, Long Island. The complainant did not possess a key to the house, nor did she have any contact information for Emma’s next of kin.

The concerned neighbor took me to the side of the house. “If you look through the window, you can see her lying in bed, but she’s not moving,” she said.

Beneath a partially-drawn shade, I observed what appeared to be a person sleeping in a bed. I tapped on the window and then checked the front and back doors, but there was no response. I used my portable radio to request a supervisor.

When I heard the voice of Sergeant Lenny Smith, the epitome of a salty cop, crackle over the airwaves, I realized my regular supervisor was probably on vacation. “Whaddya got?” he asked. I was surprised he didn’t say, “Kid” at the end of that question.

“Sarge, I’ve got an apparent natural inside a residence, but it’s secure. Can I break in?”

Sergeant Smith advised, “Ten-four—with minimal damage.”

In the rear of the home, directly above the doorknob, I broke a small corner of a multi-pane window. I reached in and unlocked the door. As I entered the kitchen, I detected the pungent odor of a kitty litter box that needed changing. Brown paper bags and groceries lined the counter top, as if someone had stopped in the middle of putting them away.

I surveyed the single-story home to see if anything was amiss. I saw nothing unusual, although I did notice several cardboard boxes stacked in the living room near the front door.

As I walked into the bedroom, I anticipated a strong odor, but there wasn’t one. I leaned down and touched her neck, searching for a pulse, but her body was cold and stiff. I felt sad for this woman who had died alone in her home; I only hoped her passing in her sleep had been painless.

I returned to the neighbor who was waiting patiently outside and confirmed that she’d been right. I gathered the necessary information for my report and thanked her for looking out for her neighbor and for contacting the police.

I asked the dispatcher to contact a PA—physician’s assistant—to respond for pronouncement.

Sergeant Smith met me at the scene. The smell of cigarette smoke clung to the uniform of the bespectacled man with a comb-over. He had a leathery look about him. I wondered if I could determine the number of years he had been on the job by counting the lines on his face —sort of like checking the rings on a tree to see how old it is.

He picked up the phone in the kitchen. “I know Emma’s family,” he said, as he dialed a number.

He reached an answering machine. In his gruff voice, he said, “Yeah, Danny? This is Lenny. Your ex-wife’s dead,” and he hung up the receiver.

I tried not to reveal my stunned reaction upon hearing this inappropriate message. I figured he must know Emma’s ex-husband fairly well to leave a message like that. I had delivered several notifications before, but they were usually made in person and always with a great deal of compassion. (Of course I’ll never forget the story a New Jersey homicide detective told me. He rang the doorbell to a home in which the television was blaring. In the gentlest manner possible, he said: “I’m sorry to tell you this, but your son’s been shot and killed in a drive-by shooting.” The man’s face fell into his hands as he sobbed. However, his tears were interrupted when he heard the jingle for the lottery drawing. He whipped out the lottery tickets from his shirt pocket, spun around, and checked his numbers.)

When the PA showed up, I led him to Emma’s bedroom. It is routine, of course, to check the corpse for obvious signs of foul play. The instant he flung back the covers to expose the body—surprise!—a screeching cat sprang out. Letting out a few colorful words, we both jumped. I don’t know who was more frightened, the cat or us.

Sergeant Smith asked me to notify Emma’s sister who lived just a few miles away. “She lives above a bar in Greenlawn with a bunch of senior citizens,” he told me.

At the sister’s residence, I met several seniors who were gathered in a communal kitchen. I learned that Abigail was out but was expected to return shortly.

“Is this about her sister?” one of the female residents asked.

I paused, wondering how anyone could possibly know about Emma already. “Yes, it is,” I said, slightly puzzled.

“Oh, she already knows,” she said, as if my visit was unnecessary.

Even more confused, I insisted, “I… I… don’t think she does.”

“Well, isn’t this about her sister, Charlotte, who died last week?”

“Charlotte? Last week? I didn’t know about that sister; I’m here about another sister—Emma!”

Abigail returned shortly thereafter. I calmly broke the tragic news to the poor woman. I extended my sincerest condolences over the loss of her two dear sisters. But if I thought the surprises of the day were through, I was wrong.

After arriving home after work, I recounted the day’s events to my husband, Joe, who said, “You won’t believe this, but I delivered those boxes you saw in Emma’s living room. Her sister, Charlotte, was a long-term tenant in one of my father’s apartment buildings.”

“You’re kidding.”

“After Charlotte passed away last week, my father asked me to bring her belongings to Emma’s house. I placed them in the living room near the front door. Oh, and I know Emma’s ex-husband, Danny. He does plumbing work for my father. We knock back a couple of beers at the Laurel Saloon every now and then. He’s probably gonna need one after hearing that message today.”

As I lay awake in my own bed that night, I thought about Emma’s cat, and wondered why he’d hidden under the covers. Had he sensed that she was in trouble? Was he protecting her? Was he waiting for her to wake up? I recalled how my own childhood pet, Catsy, used to behave whenever I cried. No matter where Catsy was in the house, she’d come running. She’d affectionately, persistently, brush up against me, sensing my sorrow and comforting me. Her soothing behavior never failed to improve my mood.

In the summer of 2007, I had the privilege of attending a Memoir Writing Workshop at the Southampton Writers Conference, taught by the master himself, Frank McCourt. While the participants were gathering one morning, someone mentioned a news report about a cat that predicted patients’ deaths at a nursing home in Rhode Island.

Upon hearing this news, I shared the story of Emma Brown and her loyal cat that had hidden beneath the covers.

Frank sat at his desk, listening.

“You have to write that story,” he said.

Oscar the cat had lived on the third floor of the Steere House Nursing and Rehabilitation Center in Providence, Rhode Island. Oscar would sniff and curl up next to a patient during the last hours of the resident’s life. He correctly sensed the deaths of more than 25 residents who suffered from Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease. When the staff realized the pattern, they were able to contact a patient’s family, enabling them to see their loved one before he or she passed away.

Oscar was honored with a plaque in recognition of his compassionate efforts. The animal behavior specialists interviewed for the story believed it possible that cats smell some chemical that is released before death, or that they can sense when their owner is upset or sick.

Perhaps that was why Emma’s cat was under the covers as death quietly called for Emma, and why Catsy soothed me as a child whenever I cried. This was what I also found comforting: that at the very least, Emma and I both knew the comfort of a warm and snuggling cat when we needed it most.

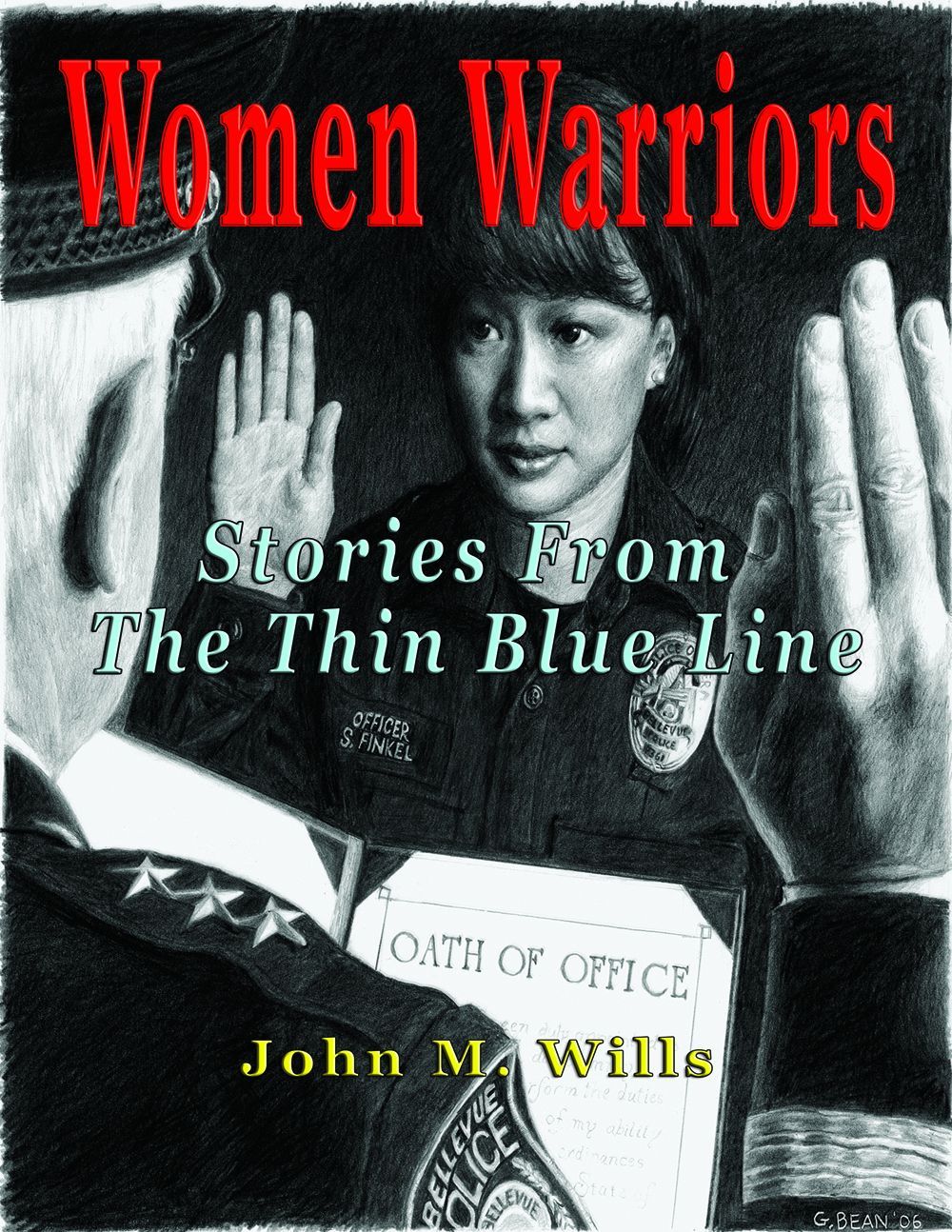

(For more by John Wills’ “Women Warriors: Stories from the Thin Blue Line” go to www.totalrecallpress.com or www.amazon.com.)